Contents

Introduction

Fiction about cricket, more generally, fiction about sport, is not an overpopulated field. Perhaps it is the case that the public nature of professional sport removes any need for a fictional version, which will mostly serve only to reproduce dramas that actually happened. Of course there have been many attempts.

Frank Keating, late of the Guardian, considered Mike (published 1909, but in 1953 divided into two stories,Mike at Wrykyn and Mike and Psmith) by P. G. Wodehouse, to be the best of these. I recall reading a cricket-themed crime novel called Testkill, co-written by former Test Captain and England Selector, Ted Dexter, in 1976. In 2010, along came an outlier; Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew was a novel by Shehan Karunatilaka, about a Sri Lankan bowler who developed a wide range of brilliant deliveries, played a few tests, had significant success but whose existence has been erased from history. This was hailed by reviewers as the first serious cricket novel ever; it won the Commonwealth Book Prize and was the only fictional work in Wisden’s 2019 listing of the best seven cricket books ever. Karunatilaka’s second novel won the 2022 Booker Prize.

Before Chinaman, though, the cricket novel most often considered to possess genuine literary merit was The Cricket Match by Hugh de Sélincourt, written in 1924. John Arlott considered it, along with Nyren’s Cricketers of My Time and CLR James’s Beyond a Boundary, to be one of the three finest cricket books. James Barrie described it as “the best book about cricket or any other game that has ever been written”. This book has been on my shelves for about fifty years, but it was only recently that I decided the time had come to read it. It so happened that this nearly coincided with the 75th anniversary of the death of de Sélincourt, so I have created this page to mark the anniversary. The text is here; I hope you enjoy it.

John Price – 20 January 2026 – jp@john-price.me.uk

The author

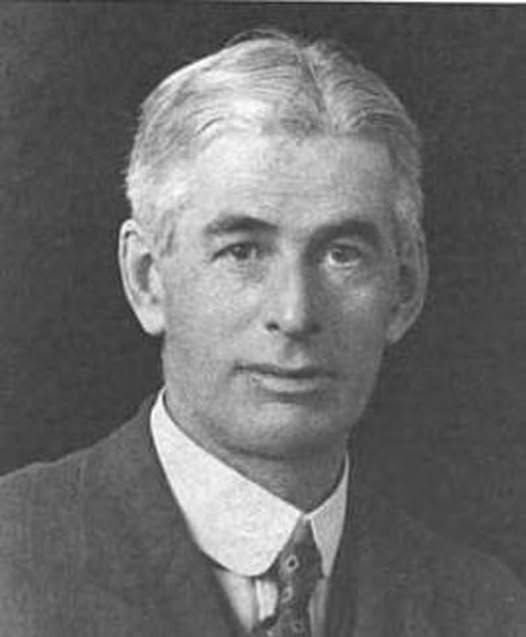

Hugh de Sélincourt was born in Hampstead, North London, 15 June 1878. His parents were Charles Alexandre De Sélincourt and Theodora Bruce Bendall. He was the youngest son of 11 children and studied at Dulwich College, the same school that PG Wodehouse attended, their times overlapping although Wodehouse was three years younger. After school, de Sélincourt went on to University College, Oxford. During the 1910s, he worked as a journalist, initially as drama critic of the Star and later as literary critic of the Observer. He continued to write book reviews for the Observer long after quitting his official post in 1914. He had also published a few light-hearted novels – the first of these, A Boy’s Marriage, came out in 1907.

He was a keen cricketer with his village club, and this was to provide material for his most important writing. In 1924, The Cricket Match was published, located in the fictional village of Tillingfold and based on his own village of Storrington at the foot of the South Downs. It was this book that was to ensure his lasting fame in an otherwise unspectacular writing career.

As well as writing sequels to The Cricket Match, de Sélincourt also wrote books about cricket generally. He died in his home in Pulborough, Sussex, on 20 January 1951 at the age of 72. His widow, Janet, died in 1955.

The story

Tillingford itself is a village in the South Downs in what is now West Sussex, closely based on the real-life village of Storrington, where de Selincourt himself used to play. The story leads us through the day, starting with early morning as the village begins to wake. We are introduced to the various players by observing their activities as they prepare for the match. The captain, Paul Gauvinier, has to spend time finding replacements for players who have dropped out. The character we focus on most, though, throughout the story is John McLeod (‘Old John’). He is an amiable, gentle individual, apparently retired, but still playing cricket as best he can, as well as administering the cricket club. On the morning of the match, he takes delivery of a package of cricket caps for him to distribute to the team. His excitement at the prospect, together with his apprehension should they not be well received by all establish him as essentially a child-like character.

The action moves to the ground as the players gather, the toss is held and Tillingford bats. Their innings is described in extraordinary detail, focusing on the feelings and character of the players as well as the cricket itself. The scorer, umpire, and off-field conversations feature prominently. Such is the detail given about Tillingford’s innings that it is possible to compile a scorecard. Indeed, there is nearly enough information to complete a full scorebook page, though I haven’t gone to that trouble. Here is the scorecard, though:

| Player | Character notes | How out | Runs | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John McLeod | Old John is a kindly, portly, retired sign-writer; also club secretary and shotless batter. | Not out | 23 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Henry Waite | New player, good cricketer, stockbroker. | Run out | 4 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Edgar Trine | Young toff, entitled but affable, reckless batsman. | Bowled | 6 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Tom Hunter | Disgruntled cycle shop owner, hits the ball hard, also opening bowler. | Bowled | 13 | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Sid Smith | Impoverished, working class, nonetheless, a real cricketer. Also, opening bowler. | Caught | 12 | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Paul Gauvinier* | Artist, public school, good all-rounder, dedicated captain. In reality, de Sélincourt himself. | Caught | 0 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | Jim Saddler+ | Enthusiastic replacement keeper. | Caught | 9 | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Dick Fanshawe | Friend of Gauvinier, working on translating a French Poem. Earnest, but not gifted, cricketer. | Caught | 7 | ||||||||||||

| 9 | Teddie White | Working class, cheerful hitter. | Caught | 8 | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Ted Bannister | Timber merchant, a huge man but not althletic and little prowess as a cricketer. | Bowled | 0 | ||||||||||||

| 11 | Horace Cairie | 15-year-old, keen on cricket and a decent batter. Came into the side as a late replacement. Represents the future. | Bowled | 13 | ||||||||||||

| Extras | 7 | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 103 | |||||||||||||||

Tillingford umpire – Sam Bird. Tillingford Scorer – Francis Allen. Fall of wickets – 1-10, 2-20, 30-37, 4-50, 5-51, 6-62, 7-28, 8-80, 9-81, 10-103

The key player is John McLeod, who, in carrying his bat through an innings, played the game of his life. His score of 23 not out is, too put it mildly, not substantial, but he prevented abject collapse, and no other batter was able to stay at the crease for any time at all. The Tillingford innings chapter is followed by a chapter of overhearing conversations in the tea room, a key part of the book which enables us to delve deeper into the mentality of the players. After describing the Raveley innings and the inevitable close finish, the novel closes with elegiac reflections about the village day ending, Old John having celebrated his achievement with a few close friends and the world of Tillingford being in balance.

Comments on the story

- Very unusually for a novel, the action of the story observes the classical unities of tragic drama, the elements of which are:

- Action – the drama should have one principal action – in this case, the cricket match.

- Time – the action in a drama should occur over a period of no more than 24 hours – everything happens on the Saturday of the Tillingford v Raveley match.

- Place – the drama should exist in a single physical location – the village of Tillingford is the location of every scene, though, it must be said, action extends beyond the cricket ground

- By no means is this a complex text. There is very little by way of plot other than a day in the lives of a village cricket team players and those close to them. There is no character development; the people we meet are the same at the end of the day as at the start.

- While we do learn a lot about the various players, we see none of them in extremis. Disappointments are minor, complaints are muted and triumphs are restrained.

- The final sentence of the novel is “Rich and poor, old and young, were seeking sleep’. It adds to a sense, never far away, that the characters we have met are little more than children having a busy day before collapsing in pleasing tiredness when it was all over. Indeed, at times I thought I was reading a school story.

- One aspect of adult society which is a persistent theme is the class structure. This is particularly emphasised in the case of Sid Smith who works hard for little reward, struggles to find respect with his wife and children and feels socially inferior to many he meets. The cricket ground, however, liberates him from such concerns, he can interact with teammates as an acknowledged star performer, the key to his side’s hopes of victory. When in whites, class differences are washed away.

- It is worth remembering that the book was written at a very turbulent time for England. The horrors of World War I are only years in the past, and the economy was far from robust. While these difficulties are occasionally hinted at, they are never allowed to detract from the overall atmosphere of peace, calm and stability.

- Whenever de Sélincourt mentions ‘old John’, I think of William Blake’s elegiac poem, The Echoing Green. I wonder if he had this in mind? Perhaps not.

Old John, with white hair

Does laugh away care,

Sitting under the oak,

Among the old folk,

They laugh at our play,

And soon they all say.

‘Such, such were the joys.

When we all girls & boys,

In our youth-time were seen,

On the Echoing Green.

Observations on the cricket

- The Tillingford total, 103, is, by modern standards (no matter what the level), a poor score, bordering on indefensible, yet here it is presented as a little over par. Runs were obviously scarcer in those days.

- I struggle a little with the character of Old John. We are told that he “used to be a sign-writer”; career change was not really a thing in 1924, so we must presume he is retired, not recently either, making him late sixties. Players can just about continue to that age, but when they do, they have to be both talented and fit; Old John is neither – the pedestrian 23 not out he makes in this match is the performance of his lifetime. He can bare run between the wickets and in the match runs out the side’s best batter. Generally, we are told, his innings don’t last long and, as he is a stone-waller, we may deduce that he can hardly ever reach double figures. So why is he a fixture in the side, let alone in the prestigious role of opener? Because he is Club Secretary, perhaps? But that would be contrary to his unselfish nature. So who knows?

- The batting order and team selection. Tillingford only use three bowlers, and they all bat in the top six. In addition, Jim Saddler, who is the replacement wicket-keeper, bats at seven. That leaves 8-11 who are specialist tail-enders. It seems a bit strange to me, especially in respect of young Horace Cairie, who is clearly one of the best batters available yet didn’t figure in the original eleven and then has to go in last, after a line of complete no-hopers. And if Saddler is good enough to bat 7, why wasn’t he in the original team?

Editions

The Cricket Match has rarely been out of print since publication. These are some of the many editions:

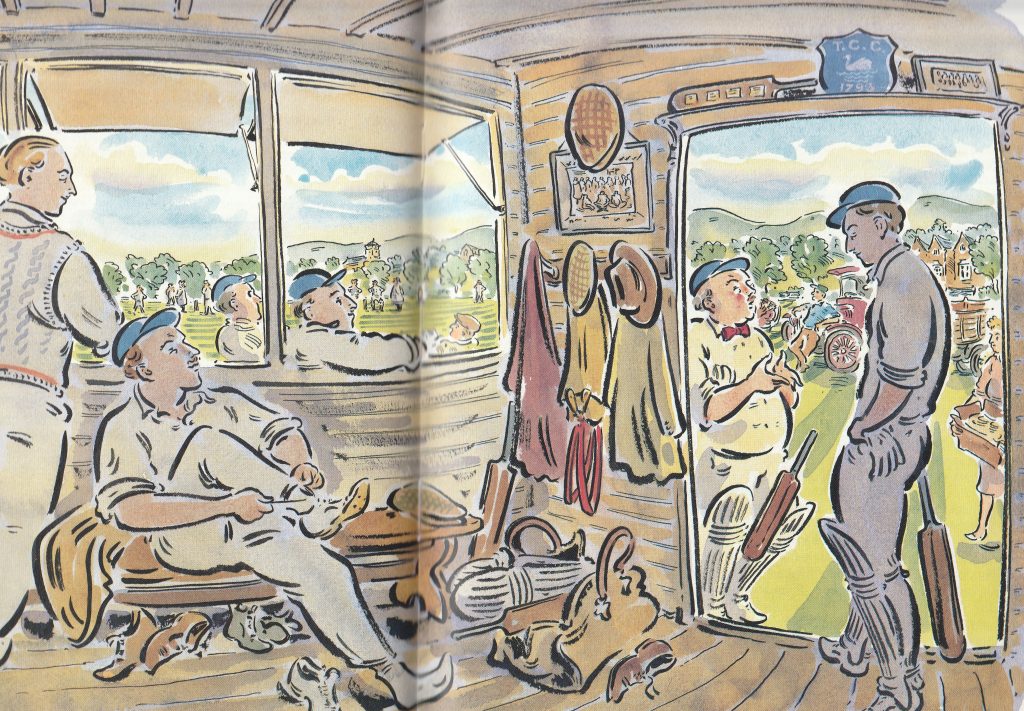

My recommendation is the 1990 edition, with great illustrations by Paul Cox. Widely available on second-hand book sites for very little outlay.

Sequels

Hugh de Sélincourt

De Sélincourt had such a success with Tillingford that, not surprisingly, he didn’t want to let it go. He returned to the village cricket team in the following writings:

The Game of the Season, (1931) – a series of short stories de Selincourt about close matches played by Tillingford, including one against the Australian touring party. The seven stories are:

- The Game of the Season

- Tillingfold Play Wilminghurst

- How Our Village Beat the Australians

- How Our Village Tried to Play The Australians

- Tillingfold v. Grinling Green

- His Last Game

- Ours is the Real Cricket!

The full text can be found here.

The Saturday Match, (1937) – one story rather than a collection, written in a lighter vein than previous Tillingford tales.

Gauvinier Takes To Bowls, (1949) – having perhaps written as much about village cricket as he was able, De Sélincourt moved his central character onto a new pursuit. It was his final book, he died less then two years after its publication.

John Parker

In 1974, the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of The Cricket Match, John Parker (journalist, club cricketer and father of eventual Test cricketer, Paul Parker), produced a similar novelette, albeit set in the world of the 1970s, featuring descendants of the original team. For instance, Tillingford is now captained by Peter Gauvinier, son of Paul Gauvinier. The writing is more brisk, reflecting later styles and we are told that certain players are sexually active – such matters would not have been regarded as fit for mention in the original work.

Subject to the above, the book closely follows the pattern of the original story. It is about the same length, is confined to one day, it all takes place in the village and the match is the only discernible plot. It was published in paperback by Penguin so must have done well in hardback.

Further reading

An article that considers further how the novel reveals much about England in the aftermath of World War I and its embrace of the pastoral setting. From: www.academia.edu.

Links about cricket fiction

- Review of Shehan Karunatilaka’s Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew

- Review of 24 for 3 By Jennie Walker

- P.G. Wodehouse and Cricket

- Article about Dudley Carew, author of The Son of Grief (1936), and Bruce Hamilton, author of Pro (1946)

- Review of Small Wonder by RK Narayan

- Review of Malcolm Knox’s A Private Man.

- Can cricket produce a great novel?

- Conan Doyle and cricket